Chaz Cone

How I got started in Ham Radio

Just off the front hall in the living room was one of those gigantic floor-standing radios with a walnut case. I think it was a Crosley all-bander:

Shortly, though, the radio was rocked back on its cabinet by a very loud signal. So loud that you could hear it squawking away far up and down the dial. As I carefully tuned it in, it was some guy talking to someone else in some kind of jargon. At least I thought he was talking to someone else -- I could only hear one side of the conversation. It was fascinating and, I reasoned, the guy must be close by as he had a southern accent and was louder than any other shortwave signal I'd heard. He said his callsign was W5TIZ, his name was Dick and his "QTH" (whatever that meant) was Little Rock. When my Dad came home from work, I told him about my new listening adventure. He said, "Oh, that's probably Dick Freeling up the street." Who? Dick Freeling lived six houses up the street at 1822 Shadowlane:

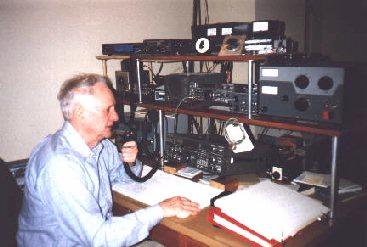

BTW, the proper name is "Amateur Radio"; there are dozens of stories of how it got to be nicknamed "Ham Radio" -- I don't think anyone knows for sure which one is true. I don't know if you remember your first friendship with an adult other than a family member, but Dick Freeling was mine. In ham lingo, he was my "Elmer", the one who introduced me to this great hobby, Amateur Radio. Dick invited me up the street to see his station (he called it his "rig" and it was in his "ham shack"). In a sunroom off the master bedroom he had a desk set up with a transmitter, a receiver, an amplifier and a bunch of other accessory gizmos. The transmitter and receiver were connected via thick black cables to several antennas in the back yard:

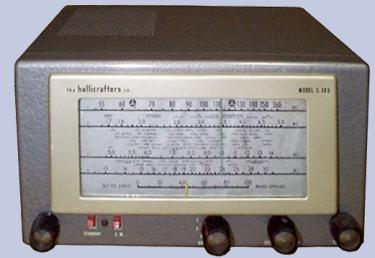

(this photo is a recent one of Dick) To become a ham, you have to get a license. There are several license classes (at the time I got involved there were five classes). The "entry level" license was the Novice Class. In 1954 you had to take a 75 question technical exam and demonstrate your ability to send and receive Morse code at five words-per-minute. (Note: The requirement to know the "code" has recently been dropped; for decades "learning the code" was the most significant barrier to the growth of Ham Radio). When you pass your ham license exam, the FCC issues you a "callsign"; the way you're known to other hams. Click HERE to read about callsigns and how they're assigned. I soon became an after-school and weekend fixture at Dick's house, helping him with tasks more easily done by someone with sight, soaking up radio lore and technique, learning the code and studying the exam questions and answers. Just two months after hearing Dick on our old console radio in the living room Dick gave me the Novice exam and I passed it. And another month after that, my license with the callsign KN5AZL arrived in the mail! Now to get "on the air" myself. I was approaching confirmation at our Temple and I begged my (rich) Uncle Dave to buy me a receiver as a confirmation gift -- a first step to setting up my own station. My folks had already agreed to my stringing a wire antenna through the trees in the back yard. Uncle Dave came through with the radio, a Hallicrafters S38-D:

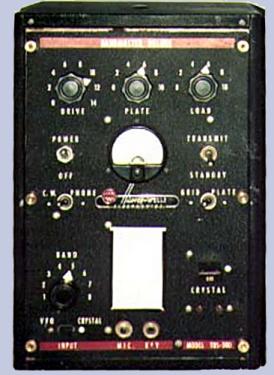

Wow! A receiver and an antenna! I could listen -- but I couldn't "talk" without a transmitter. My mom came through; I "helped" her find a used Harvey-Wells TBS-50D "BandMaster" transmitter for $75.00:

The Novice class license which I had earned only permitted transmission via Morse code. You'd tap out the callsign of the station you were calling and, when/if they responded, you'd exchange names and locations (location? So that's what "QTH" meant! Click HERE to read about ham "Q" signals.) all by operating a radio-telegraph key. Here's my first key (I still have it):

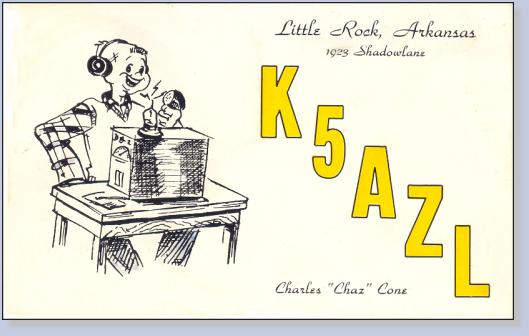

Hams confirm contacts by mailing postcards (called "QSL" cards) back and forth; many are quite colorful and paper the walls of "ham shacks" world-wide. Here's my first QSL card (circa 1954):

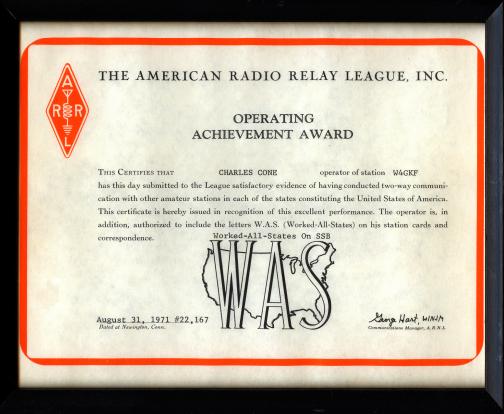

The governing body of Ham Radio in the US is the American Radio Relay League (ARRL) and they provide a number of operating awards to demonstrate proficiency. The first one most new hams go after is "Worked All States" (WAS). To earn that one, you have to contact at least one ham in each of the fifty states and receive a QSL card from each state. The WAS Certificate is just a 8.5x11 piece of paper but, boy, was I proud to earn it!

(Sharp eyes will notice this is the WAS I earned as W4GKF some years later..) 1954I often had chats with Dick on the radio, sometimes in code and sometimes with him using voice and me using the code. One school night in October about 11pm Dick asked me (on the radio) to give him a call on the telephone. He asked if I could walk up to his house. It's a school night and I'm just fourteen but off I went (I didn't tell my folks I was going out, of course). When I got to Dick's house he was sitting on the front porch with a big battery-powered all-band Zenith shortwave receiver:

In those days radios like that were about the size of a suitcase and weighed twenty pounds or so. For weeks we'd both been annoyed by very loud static on the ham bands; static that we'd not heard before. The static came on at about 8pm and stopped early in the morning. It really interfered with our enjoyment of the hobby. He told me he thought that the static was coming from somewhere in the neighborhood (it was so loud) and that tonight we were going to find the source. How? Well, he said, we'd walk through the alleys behind the houses in the neighborhood. He'd listen to the radio with headphones while I climbed over the fences and pull the main power switch of each house, counted to ten and switched it back on. The theory was that we'd find the house that way when the static stopped. Got the picture? A kid and a blind man wandering the alleys, turning power off and on at houses. Lucky we weren't shot or arrested. But we found the house. It was two houses from my house on the cross street, Club Road. The next day Dick called the people who lived there and said the he'd "found" that something in their house was causing static and interfering with the hobby of the "poor, blind man up the street". They agreed to a visit that evening. Sure enough, the noise started about 8pm. The family had recently had a grandmother move in with them. Each night when she went to bed she turned on her heating pad. A wiring defect in the pad generated the static! Dick bought her a new heating pad and the static was gone for good.

Neighborhood ConcernOne last Dick Freeling story. Like most hams, Dick liked to tinker with his equipment and antennas. His principal antenna was at the top of a 57' windmill tower in his backyard:

The neighbors were apalled that a blind man was climbing nearly six stories in the air and working up there for an hour or so. They'd gather and stare in horror as this "poor man" climbed up there. After a few such episodes a delegation went to Dick and explained that it worried them so much when he did this. In characteristic Dick fashion he said, "No problem; I'll do it at night -- it's all the same to me." And, thereafter, he did!

Here's Dick in August 2004

In less than six months I successfully sat for the General class exam and code test and passed it. Besides being able to drop the "N" from my callsign and becoming K5AZL, I now had voice privileges on most amateur bands. To read a short discourse on "ham bands", click HERE Ham Radio has dozens of sub-specialties one can get involved in. For example, some like designing and building their own radios. Some like "rag-chewing" (just chatting with others around the country and world and sharing interests). Some like contesting (seeing how many stations/countries/counties you can work in a fixed time-frame) and so forth. For me, the attraction was always talking with stations far, far away. Distance (in ham lingo) is called "DX" and "working DX" was and is my special passion. Of course, there are a lot of variables affecting one's ability to "work DX". Those variables are:

I was quickly able to confirm contact with hams in fifty different countries. This might sound harder to do and more impressive than it really is. A "country" (for Ham Radio purposes) is more liberally defined than you might think. In addition to the definition of a country that you're familiar with (that is, a sovereign government), a place can exist as a Ham Radio country even if it's not a sovereign government if it is located a good distance from its government. For example, Puerto Rico wouldn't be thought of as a separate country by most standards -- but it qualifies as a separate country by the "far from home" rule. To clear up the "country" confusion, we call these places "entities". Presently there are 338 "entities" for Ham Radio purposes. The point is that working fifty countries isn't all that difficult. Heck, the US, Canada, Puerto Rico and even Alaska and Hawaii all count as separate countries for Ham Radio purposes. At that time there were 320 countries possible -- and I only had fifty.. It didn't take long for the limitations of my transmitter, receiver and antenna to make it hard to work a new country. What to do, what to do? Enhance the station! In the list above you'll notice that the first two items are pretty much out of your control. The third (a better antenna) was out of a 15 year-old's control, too. I wanted to put up a tower and a "beam" antenna (something like this one):

1955By now I'd reached the advanced age of fifteen and needed $189.50 to buy my dream transmitter, the Heathkit DX-100:

Read on for my high school Ham Radio experiences..

|